Decirlo todo. Juan Carlos Bracho/Pieter Vermeersch. «Jugadas a tres bandas». Galería Pilar Serra. Comisario Óscar Alonso Molina. Madrid 2015

descargar pdf

El grado cero de enunciación es ellímite al que tiende el trabajo de los dos artistas seleccionados. El resultado de su confrontación es un diálogo en sordina, un rumor de fondo, una lucha de miradas fijas sostenida en silencio, donde el marco que los reúne -el espacio físico de la galería, su arquitectura-, se convierte en un elemento activo de esos significados apenas enunciados. Un efecto barroco inesperado donde “no decir nada puede decirlo todo” (B. Gracián).

Gracián sabía que, frente a esa hidra vocal que es la palabra, “no decir nada puede decirlo todo”. Y así, de cada fragmento desgajado del discurso surgen nuevos significados donde el vuelo del sentido se amplía a medida que el significante se comprime, se recorta, se astilla, se consume… Las interpretaciones a que ha sido sometido el pequeño papel arrugado encontrado en el bolsillo de la americana de Nietzsche tras su muerte encarnan el caso por excelencia: “He olvidado mi paraguas”, dejó escrito allí, nadie sabe a ciencia cierta si como recordatorio práctico para recuperarlo o como cifra arcana en que se concentró el poder póstumo de su pensamiento. Hipótesis, alegorías, libros enteros dedicados a ese pensamiento suelto, al cual se ha contrastado violentamente con todo el edificio filosófico de su autor, dando lugar a interpretaciones de lo más disparatadas…

Es el vacío que rodea todo punto de atención lo que hace crecer la fascinación de lo que éste pudiera decirnos. En mitad del desierto, un escarabajo andando sobre la arena ardiente cobra una dimensión inesperada, concentrando nuestra atención en su minúscula presencia, mientras el efímero rastro que deja sobre la arena en movimiento y barrida por el viento adquiere la potencia del emblema que demanda cierta interpretación radical. También en esta exposición podemos comprobar cómo la densidad alusiva de la imagen crece a medida que sus figuras se evaporan y que el grado de “abstracción” aumenta. Robert Rosenblum afirmaba incluso que cuanto menos hay que ver en una imagen más es lo que es necesario decir sobre de ella. El discurso, pues, aparece y desaparece en un movimiento reflejo, en un vaivén estroboscópico que, como la Esfinge, nos reta: “descíframe o te devoro”.

Los trabajos de Pieter Vermeersch y de Juan Carlos Bracho poseen en común una acusada tendencia a acercarse al grado cero de enunciación en sus piezas: a no decir nada por decirlo todo. Imágenes en apariencia vacías, afásicas, autorreferenciales y un tanto herméticas, que de manera muy analítica inciden en las fronteras de aquella herencia tardomoderna ligada al formalismo de la abstracción postpictórica y en los límites contemporáneos de una categoría romántica por excelencia, como es la de lo sublime.

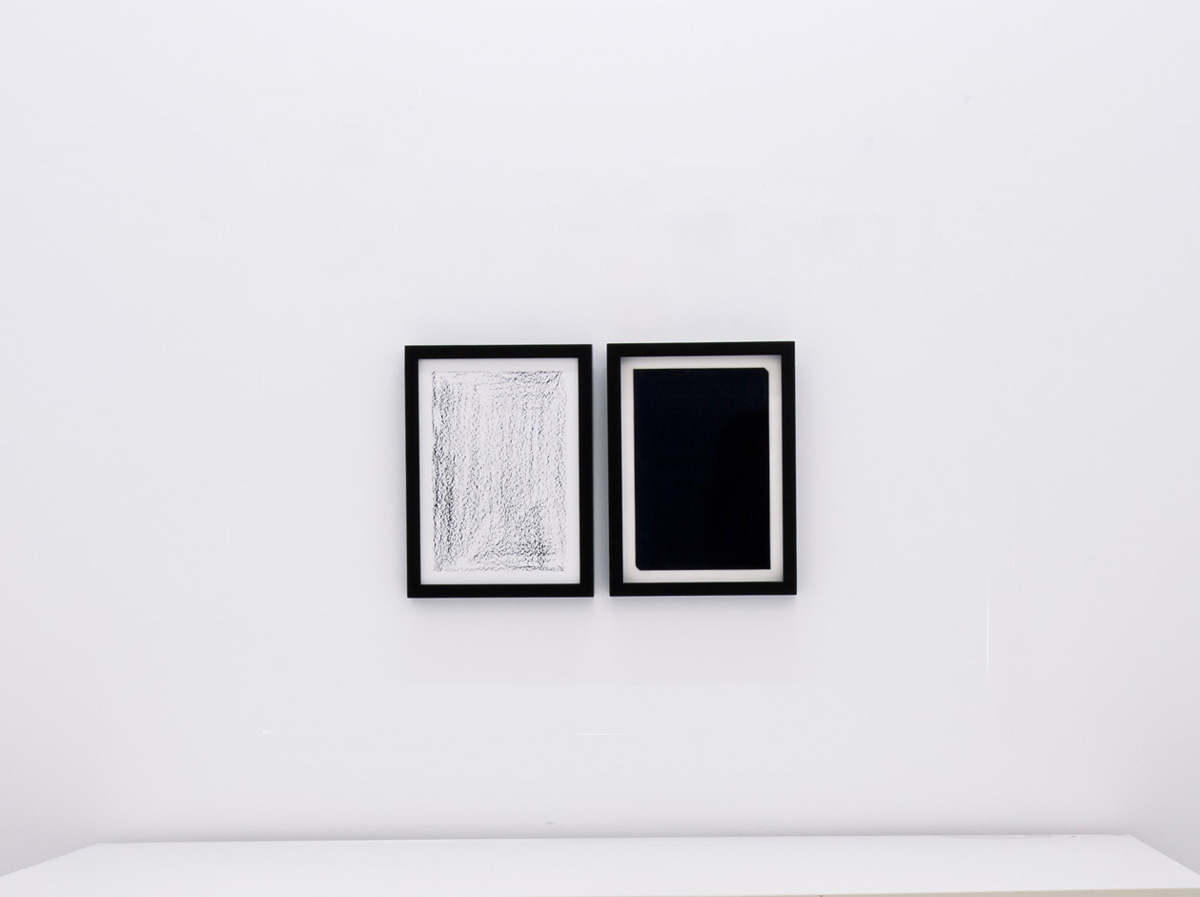

Si el primero parte para ello a menudo de un bucle de relectura procesual, en el cual el artista fotografía de cerca (pérdida de la perspectiva ya negada de antemano) la superficie de sus propias pinturas monocromas, para luego volver a intervenir el papel fotográfico con barridos de pintura, el segundo, mediante frotados y catas, revela las capas de pintura que se superponen en la superficie del muro sobre el que realiza a menudo sus intervenciones. Las referencias de Vermeersch a la arquitectura son constantes en esos muros cegados, esos encofrados o cierres ante la mirada que no puede traspasarlos; lo mismo que ocurre en la sutil labor de arqueólogo de Bracho, recogiendo en sus frotages las huellas verticales que acumula el plano de representación más neutro y desatendido: la propia pared expositiva.

No decir nada puede ser, en efecto, la estrategia adecuada para que el espectador proyecte una miríada de interpretaciones sobre estas obras ancladas en el proceso y en el análisis de los propios medios que estructuran la imagen y su visión. El mundo entero cabe allí: su cifra y su desciframiento; su enigma y su revelación. Imágenes al cabo de una contención propia del conceptismo barroco, que aspiran a ser, en su neutra y contenidísima encarnación, emblema de un universo más allá de lo sensible que todavía puede decirse, articularse por imágenes. Precisamente en su Criticón, ese texto increíble, dedicado a la contemplación total del universo humano y espiritual desde una perspectiva apenas anclada en el cuerpo, cuyos protagonistas presiden las más portentosas escenas sin apenas desarrollo de su propia historia y sin que podamos estar seguros de su dimensión física (parecen más bien espíritus, seres que son sólo ojos, puras ideas…), podemos leer aún a Gracián: “Advertid que va grande diferencia del ver al mirar, que quien no entiende no atiende: poco importa ver mucho con los ojos si con el entendimiento nada, ni vale el ver si el notar. Discurrió bien quien dijo que el mejor libro del mundo era el mismo mundo, cerrado cuando más abierto; pieles extendidas, esto es, pergaminos escritos llamó el mayor de los sabios a esos cielos, iluminados de luces en vez de rasgos y de estrellas por letras.” Y, así, como veis (porque veis), no tengo nada más que deciros.

Ó.A.M. [Naz de Abaixo, Lugo, enero 2015]

Say it All. Juan Carlos Bracho/Pieter Vermeersch. «Jugadas a tres bandas». Pilar Serra Gallery. Curator Óscar Alonso Molina. Madrid 2015

download pdf

The degree zero of statement is the limit to which the work of the two selected artists tends towards. The result of their confrontation is a muffled dialogue, a background murmur, a fight of fixed stares maintained in silence, where the frame which unites them – the physical space of the gallery, its architecture – becomes converted into an active element of those meanings scarcely stated. An unexpected baroque effect where “by saying nothing one can say it all” (B. Gracián).

Gracián knew that, when faced with that verbal hydra which is the word, “by saying nothing one can say it all”. And so, from each torn off fragment of the discourse there arise new significances where the flight of the meaning expands to the degree that the significance is compressed, cut back, splintered, consumed… The interpretations that have been made of the small wrinkled piece of paper found in Nietzsche’s jacket pocket following his death embody the case par excellence: “I have forgotten my umbrella”, he wrote, and no one knows for sure whether it was written as a practical reminder for him to retrieve it or an arcane code that concentrated the posthumous power of his thought. Hypothesis, allegories, entire books devoted to that flowing thought, which has violently contrasted with the entire philosophical edifice of its author, giving rise to the most disparate interpretations…

It is the vacuum that surrounds any point of attention that causes the fascination of what this could be saying to us to grow. In the middle of the desert, a beetle walking on the burning sand takes on an unexpected dimension, focusing our attention on its miniscule presence, while the ephemeral trace that it leaves on the sand moving and swept by the wind takes on the power of the emblem that demands a certain radical interpretation. In this exhibition too, we can confirm how the allusive density of the image grows as its figures evaporate and the degree of “abstraction” increases. Robert Rosemblum even claimed that when there is less to see in an image the more necessary it is to talk about it. Discourse thus appears and disappears in a reflex movement, in a stroboscopic flicker which, like the Sphinx, challenges us: “decode me or I will eat you”.

The works of Pieter Vermeersch and Juan Carlos Bracho have in common a sharp tendency to approach the degree zero of statement in their pieces: to say nothing in order to say it all. Images that appear to be empty, aphasic, self-referential and somewhat hermetic which in a very analytical way impinge on the frontiers of that late-modern legacy tied to the formalism of the post-pictorial abstraction and on the contemporary limits of a romantic category par excellence, as is that of the sublime.

If for this the first artist usually starts from a cycle of procedural rereading in which he photographs from close up (loss of the perspective already denied previously) the surface of his own monochromatic paintings in order to then intervene on the photographic paper with sweeps of paint, the second reveals by means of rubbings and samples the layers of paint that are superimposed on the surface of the wall on which his interventions usually take place. The references which Vermeersch makes to architecture are constants in those blind walls, those formworks or enclosures, regarding the look which cannot pass through them; the same occurs in the subtle archaeological work of Bracho, in which his frotages contain the vertical traces accumulated by the most neutral and neglected plane of representation: the actual exhibition wall itself.

Saying nothing can in fact be the right strategy for the spectator to be able to project a myriad of interpretations on these works anchored in the process and in the analysis of the actual means that structure the image and its vision. The entire world fits in there: its coding and its decoding; its enigma and its revelation. Images at the end of the actual containment of baroque conceptualism, which, in its neutral and highly contained incarnation, aspire to be the emblem of a universe beyond what can be sensed which can still be said, articulated by images. It is precisely in his Criticón, that extraordinary text, dedicated to the complete contemplation of the human and spiritual universe from a perspective that is scarcely anchored in the body, whose protagonists preside over the most prodigious scenes with hardly any development of their own history and without our being able to be sure of their physical dimension (they seem rather to be spirits, beings that are just eyes, pure ideas…), that we can still read Gracián. “Be warned that there is a great difference between seeing and looking, that he who does not understood does not heed: Little does it matter to see much with the eyes if it is without understanding, nor is seeing of any use without noting. He argued well who said that the best book in the world was the world itself, closed when it is most open; spread out skins, in other words, written parchments was what the greatest of the wise called those skies, lit with lights rather than strokes and with stars rather than letters.” And so, as you all can see (because you all can see), I have nothing more to say to you.

Ó. A. M. (Naz de Abaixo, Lugo, January 2015)